This post was originally published on the Interaction Institute for Social Change’s blog by Curtis Ogden on March 7, 2013. It is offered as a Food Policy Resource for the “Overview of Collective Impact & Its Application for Food Policy Councils” Webinar.

In a fascinating article in Fast Company, entitled “The Secrets of Generation Flux,” Robert Safian acknowledges that in these uncertain economic times, there is no single recipe for success. Safian profiles a number of leaders who have been relatively successful at riding the waves in different ways, and notes that they are all comfortable with chaos, trying a variety of approaches, and to a certain degree letting go of top-down control. This resonates with our experiences at IISC helping people to design multi-stakeholder networks for social change. For example, even in a common field (food systems) and geography (New England) we witness different forms emerge that suit themselves to micro-contexts, and at the same time there are certain commonalities underlying all of them.

The three networks I wanted to profile in this post exhibit varying degrees of formality, coordination, and structure. All are driven by a core set of individuals who are passionate about strengthening local food systems to create greater access in the face of food insecurity and growing climate destabilization. They vary from being more production/economic growth oriented to being more access/justice oriented, though all see the issues of local production and equitable access as being fundamentally linked and necessary considerations in the work.

Vermont Farm to Plate Network

The Farm to Plate (F2P) Initiative, was approved at the end of the 2009 Vermont legislative session and directed by the Vermont Sustainable Jobs Fund, in consultation with the Sustainable Agriculture Council and other stakeholders. Its initial charge was to develop a 10-year strategic plan to strengthen Vermont’s food system. This was done over a 2-year period with input from hundreds of stakeholders from around the state. The Farm to Plate Network officially launched in 2011, borrowing heavily from the structure of the RE-AMP Network in the Midwest, a multi-organizational effort to fight climate change.

The Farm to Plate (F2P) Initiative, was approved at the end of the 2009 Vermont legislative session and directed by the Vermont Sustainable Jobs Fund, in consultation with the Sustainable Agriculture Council and other stakeholders. Its initial charge was to develop a 10-year strategic plan to strengthen Vermont’s food system. This was done over a 2-year period with input from hundreds of stakeholders from around the state. The Farm to Plate Network officially launched in 2011, borrowing heavily from the structure of the RE-AMP Network in the Midwest, a multi-organizational effort to fight climate change.

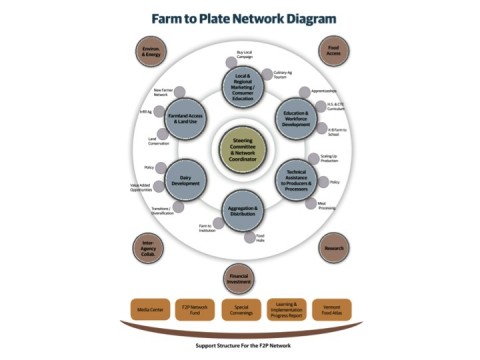

The structure was fairly well defined in advance, given F2P’s mandate from state government to double production and the clear need for coordination around the Network’s robust strategic plan and 25 goals. It currently features Working Groups (WG) focused on Farmland Access & Stewardship, Dairy Development, Aggregation & Distribution, Technical Assistance, Education & Workforce Development, and Consumer Education & Marketing. Each organized around associated pieces of the strategic plan with flexibility to add and adjust. In addition there are Cross-Cutting Teams (CCT) focused on topics such as Food Access, Policy, and Research and Funding.

It is at the WG and CCT level where most of the “action” happens, taken from a 15,000 foot view to help coordinate and fill gaps on the ground. A Steering Committee comprised of members of the Working Groups and others “holds the whole” from more of a 30,000 perspective, trying to maintain as broad a view of the food system as possible. There are a few paid staff who support the Network through weaving, communications, coordination and the like. The Network is also about to launch the “Food System Atlas” which will showcase stories, videos, job listings, news, events, resources, the F2P Strategic Plan, people, and organizations that are strengthening Vermont’s food system.

Rhode Island Food Policy Council

The story of the Rhode Island Food Policy Council revolves largely around the Southside Community Land Trust, an urban land trust that has been an agent for community food security, providing land, education, tools, and support for people to grow food for themselves in greater Providence. SCLT applied for and received funding from a few local foundations to facilitate the collaborative efforts of a multi-stakeholder Design Committee to develop a vision and mission for the future RI Food Policy Council (RIFPC) and determine the Council’s structure, membership and by-laws. Unlike the process in Vermont, the Design Committee refrained from engaging in a full-fledged strategic plan and instead enlisted the services of Karp Resources to conduct a comprehensive Community Food Assessment of Rhode Island to provide a baseline description of the state’s food system and identify priorities for the RIFPC and other stakeholders working to increase community food security. The decision was also made to formally remain separate from any state entity, while building connections to the Agricultural Partnership and recently formed Interagency Food and Nutrition Policy Advisory Council.

The story of the Rhode Island Food Policy Council revolves largely around the Southside Community Land Trust, an urban land trust that has been an agent for community food security, providing land, education, tools, and support for people to grow food for themselves in greater Providence. SCLT applied for and received funding from a few local foundations to facilitate the collaborative efforts of a multi-stakeholder Design Committee to develop a vision and mission for the future RI Food Policy Council (RIFPC) and determine the Council’s structure, membership and by-laws. Unlike the process in Vermont, the Design Committee refrained from engaging in a full-fledged strategic plan and instead enlisted the services of Karp Resources to conduct a comprehensive Community Food Assessment of Rhode Island to provide a baseline description of the state’s food system and identify priorities for the RIFPC and other stakeholders working to increase community food security. The decision was also made to formally remain separate from any state entity, while building connections to the Agricultural Partnership and recently formed Interagency Food and Nutrition Policy Advisory Council.

With an eye towards inclusiveness and nimbleness, the Design Committee created a structure that features, at this point, four Work Groups focused on the core visionary goals of the RIFPC: Access, Production, Environment, and Economy. These Work Groups were launched in a very open public meeting, with people essentially voting with their passions, and they have continued to welcome newcomers. No formally established goals or strategies were handed over to the Work Groups, so as to let them find their own footing and interests under the overarching visionary goals. The core elected group of Council members has as part of its role to provide support and high level guidance to these Work Groups. Part-time paid staff support exists for a network coordinator and communications expert, both of whom help to maintain an evolving website. At this point the Council is trying to balance the need for more of a centralized function around advocating in a timely way for policies impacting the food system, with an ongoing openness and fluidity to its public meetings and Work Group activity.

Connecticut Food System Alliance

The Connecticut Food System Alliance was born of food system advocates from around the state coming together from time to time to discuss and share information. Gradually, desire grew to have more than just an annual gathering. With limited funding, a core “design team” came together to think about how to create more grassroots momentum that would complement the Governor’s Council for Agricultural Development, which is spear-headed by the Commissioner of Agriculture and is broader in scope than food systems and security. Over the past 6 months, this design team has pulled together two large and diverse convenings of people from around the state to get to know one another, “close triangles”, share insights, and talk about how to create more significant and shared value. This has taken the form of an “alignment network,” uniting under what is now a shared vision and guiding principles, and connected by a listserv.

During the last convening, we facilitated an Open Space forum for people to identify key areas of inquiry and action that they might want to pursue. These varied from a pilot project tackling food insecurity in one town to strengthening farm-to-institution efforts to growing and diversifying network membership, to exploring the root causes of what ails the food system. Volunteer facilitators have stepped up to lead these nascent “task teams” and the volunteer design team has morphed into a larger “Network Support Team” to provide support to these teams and organize future gatherings. Another convening is in the works for late spring with considerations about whether or not it makes sense to pursue grant funding for more support.

The entire process of CFSA to date has been very emergent, aptly described by Adrienne Marie’s words and spirit in the post from two days ago:

“emergence is the way complex systems and patterns arise out of a multiplicity of relatively simple interactions. rather than laying out big strategic plans for our work, many of us have been coming together in community, in authentic relationships, and seeing what emerges from our conversations, visions and needs.”

Common Ground

None of this is to say that any of these approaches is more “right” than the other. Each has its benefits and challenges, and each fits its particular circumstances. All are open to changing as context demands. From one perspective we might see the VT Farm to Plate Network as the most formal and structured with the CT Food System Alliance as the most fluid and emergent, and the RI Food Policy Council as lying somewhere in-between. The differences are important to note, as are some of the likely underlying contributing factors such as funding, “home,” partnerships, tangibility or simplicity of outcomes, diversity of stakeholders, and the existing eco-system of actors and initiatives in the system.

At the same time it is also important to note that underlying all of these network forms is an important network ethic, or way of thinking, that I would summarize in the following way. It is an awareness that to the extent that there is a network “center” it is about being in service of and helping to connect the whole, as well as bring in the “periphery;” there is an emphasis on contribution and creating value over deferring to credentials and the usual suspects; people lead with a spirit of openness; and there is an overall effort towards growing the pie, not just carving it up into smaller pieces. And there is certainly a developmental trajectory to engaging in net work, as evidenced in these and all network initiatives we’ve supported, such that trust-building, transparency, and generosity are always works in progress. This is what forms the intangible and enriching ground of these and other forms that will hopefully help create real and necessary collective impact and transformation.

Curtis Ogden is a Senior Associate with the Interaction Institute for Social Change (IISC) and facilitator for the FSNE Network Team. He supports a variety of food system-focused networks through his work at IISC. Curtis lives in Amherst, MA with his wife and three daughters.