In our region, the Connecticut River Valley in Massachusetts, there is a lot of talk right now amongst community food organizations about the whiteness of the majority of people leading those organizations, and what that means in building an equitable, resilient food system.

There’s also talk about the Farm Bill reauthorization (which is underway right now) and the impact it could have on communities of color who most need our valued nutrition programs. How do we talk about racial equity and the Farm Bill within our communities, and with our policy-makers?

Practice

I’ve been working with colleagues to identify tools to build shared understanding and create pathways to local leadership for the communities most impacted by lack of access to healthy, affordable food. Together with colleagues in the PVGrows network, we have been holding conversations with members of white-led community food systems organizations to get at the uncomfortable and necessary work we white folks have to do to be strong collaborators in racial equity change-making.

These conversations can be messy and awkward, sometimes painful. We begin with understanding white supremacy habits. How do our privilege and our often hidden biases manifest, even when our intentions are genuine? Here are some of the tools and ideas we’re using:

- Reframe and read history. Ta Nahisi Coates’ The Case for Reparations; Howard Zinn’s A People’s History of the US; Leah Penniman’s Four not so easy ways to dismantle racism in the food system; Shorlette Ammons’ Shining a Light in Dark Places;

- Encourage white folks to do our work and examine patterns. A number of us are working with White Supremacy Culture, by Kenneth Jones and Tema Okun. Peggy McIntosh has a terrific chapter called Too Much History Between Us in Unlikely Allies in the Academy;

- Separate intent vs. impact. It’s easy to try to justify when we white folks miscommunicate or dominate a conversation. Instead, work to pause, listen, see the impact from another’s point of view;

- Advocate for public policy that supports racial equity. Follow HEAL Food Alliance, Union of Concerned Scientists’ Farm Bill recommendations. Follow Race Forward/Center for Social Inclusion.

I do this work because I believe it is the only way to be – not only as a food change-maker but completely and fully in my life. I have hope. Hope that my fellow white food change-makers will have these conversations with and among other white people. We must become skillful, artful and be able to lead from the heart as if our future depends on it, because it does.

Policy

As the Farm Bill is up for reauthorization right now, some ask “What do the Farm Bill and racial equity have to do with each other?” The Farm Bill is a major piece of legislation that doesn’t get enough attention, but determines so much about our health and environment. A small portion of people in this country actually farm (only about 1% of our population). In order to understand the Farm Bill and what it has to do with racial equity, we have to know a little about the history of land ownership in the US.

People of color have been systematically excluded from building wealth. “40 Acres and a Mule” is an example: when enslaved people were freed after the Civil War, they were promised 40 acres and a mule. It didn’t happen. Few Black farmers were able to stay on land they owned due to violence and local injustices. Yet in 1920, 20% of farmers in the US were African American. In 2012, only 1.4% of the total farmers in the US were African American. Significant displacement has occurred over the last 100 years resulting in over 14 million acres of Black land loss. Diminished Black land ownership continues to be a result of policies that make it difficult for farmers of color to acquire loans and build equity. (Penniman)

The policies that protect and promote large scale farming are a direct result of the 1862 Homestead Act, which originated during the Civil War and resulted in the legal land grab by whites from Native Americans (meaning any adult head of household – white male – who lived and cultivated land for more than 5 years was entitled to own it). (Salvador)

The Farm Bill has been shaped by agribusiness and commodity groups, making it difficult for farmers trying small sustainable ventures to get into farming, to make a living at it, and to produce diversified crops. The inequities built into this system are obvious and blatant: a small number of large farms produce a limited variety of crops, mainly corn, cotton, wheat, and soybeans. Crop supports incentivize farmers to grow these subsidized crops to the exclusion of vegetables and fruits. Products derived from corn, soybeans, and wheat are cheap because of subsidies, which leads to their overuse in processed foods in the form of corn syrup and cooking oils. Processed foods are cheaper in price and lower in nutritional value than fresh produce, and are more available in communities with fewer supermarkets. As a result, we are threatened by diet related illnesses, which hit harder those with less access to healthy fresh foods.

Despite how hard it is to get into farming and make a living, according to Leah Penniman, the number of Black farmers is growing: “In 2012, the number of Black farmers in the United States was 44,629. This was a 12 percent increase percent since 2007. While extremely low, these numbers are shifting, due to the energy and leadership of powerful people of color farming and working for food systems change.” (Penniman) Many communities are designing their own solutions to food resilience (some which are funded through Farm Bill project allocations): urban farms and gardens, mobile farmers markets, healthy corner store promotions, farm to school initiatives, and new models for cooperative land acquisition and ownership.

So why is the Farm Bill so important right now?

In the wealthiest nation, we need robust programs to build land ownership opportunities for all people, financial incentives to grow fruits and vegetables, and nutrition programs that provide healthy food to everyone and a pathway to resilience and self-sufficiency.

What has this to do with race? Food insecurity (not having reliable access to enough affordable, healthy food) harms health, the ability to learn, productivity, and in turn the nation’s economic strength. (FRAC, USDA). Food insecurity disproportionately affects households with children, Black and Hispanic households, rural communities, and the South. (Overall, one in six households with children are food insecure.)

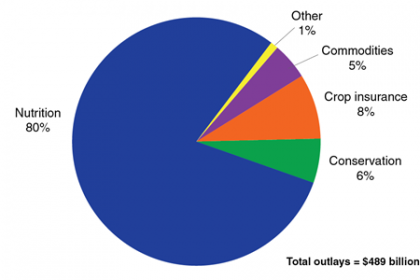

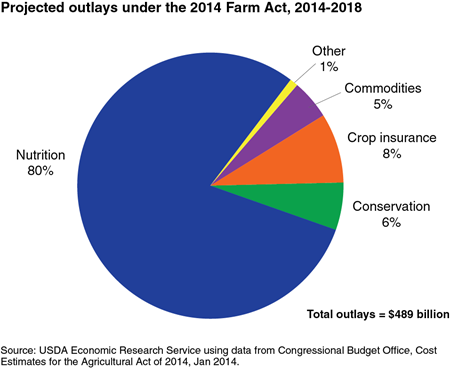

The Farm Bill is an enormous piece of legislation that includes land protection, production and nutrition programs. The joining of these programs aligns partners across party lines. This is good and offers the ability to change the way we think about food and health. However, powerful large-scale farm lobbies have strong influence in maintaining crop insurance, subsidies, and controls, and in influencing nutrition – anti-hunger (Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program – SNAP) funding.

In addition to funding our country’s vital hunger safety net, the Farm Bill encompasses programs that support Socially Disadvantaged and Beginning Farmers and Ranchers, Veteran Farmers, Food Insecurity Nutrition Incentives, and farmers’ market promotions. These are the vital programs that fund community food projects designed to reach under-resourced neighborhoods, such as the Healthy Incentives Program that was so successful in Massachusetts last year, urban farms, food hubs, and mobile markets, to name a few. These, along with “specialty crops,” are all in just 1% of the funding for the Bill.

In addition to funding our country’s vital hunger safety net, the Farm Bill encompasses programs that support Socially Disadvantaged and Beginning Farmers and Ranchers, Veteran Farmers, Food Insecurity Nutrition Incentives, and farmers’ market promotions. These are the vital programs that fund community food projects designed to reach under-resourced neighborhoods, such as the Healthy Incentives Program that was so successful in Massachusetts last year, urban farms, food hubs, and mobile markets, to name a few. These, along with “specialty crops,” are all in just 1% of the funding for the Bill.

Millions of Americans struggle to find work that pays enough for their families to live, and this is especially true in communities of color in many urban areas as well as for people in remote rural areas. Everyone wants a food system that provides healthy, fresh, affordable food, and yet this Farm Bill will dramatically cut the nutrition programs that feed our most vulnerable populations.

Why is Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) so important? SNAP:

- Reduces poverty and deep poverty;

- Supports economic stability and academic outcomes;

- Reduces food insecurity;

- Protects against obesity;

- Improves dietary intake;

- Improves health outcomes; and

- Improves mental health outcomes.

(FRAC Newsletter, December 2017)

The House of Representatives recently voted to block a highly contentious proposed Farm Bill that would have reduced SNAP spending by an astronomical $217 billion over 10 years, which would have resulted in reducing assistance sharply for tens of millions of seniors, children, people with disabilities, working families, unemployed people, and veterans.

Participation in SNAP rises during economic downturns and falls when the economy picks up. SNAP is one of the most responsive federal programs in assisting families and communities during economic downturns and lifting people out of poverty. Cuts to SNAP whether they come as proposed structural changes (such as strict work requirements impacting eligibility, the suggestion of a return to pre-packed boxes, or as block granting state by state), are demeaning and potentially dangerous attacks on a program that requires more funding, not less. (FRAC)

Ruth Tyson from the Union of Concerned Scientists writes: “We need a more inclusive farm bill that ensures that from farm to fork our food system supports healthy people, local economies and the environment. To start, we need more diverse voices at the table, including consumers, farmers of color, food hubs serving rural and urban communities, and farmers and ranchers who are rebuilding soil health.”

What happens next?

In mid-June the Senate Agriculture Committee is expected to release text on their expected draft. By the end of June, the House version of the Farm Bill is expected to be voted on again, despite having already failed on May 18.

What can we do?

We need a Farm Bill to pass to fund many of our valuable programs that support small, sustainable equitable food and farming.

We need a Farm Bill to pass to fund many of our valuable programs that support small, sustainable equitable food and farming.- Right now, we can let our policy-makers know that we won’t stand for SNAP reductions, environmental degradation, or loss of our valuable programs that reach all people with the possibility of changed lives.

- Write Congress now and ask for a better Farm Bill. Follow National Sustainable Agriculture Coalition’s Farm Bill Blog for updates.

- Build personal, anecdotal, success stories, and share them with your elected officials and their staff.

- We can also work to cultivate local leadership and advocacy channels.

It’s time to demonstrate to our policy makers the success of these programs, to illuminate the historical perspectives that have been the building blocks of our current broken systems, and to demand that we move forward in ways that support everyone.

And white folks in the food change movement, our colleagues of color know that justice work never ends. Keep engaging deeply with open hearts in understanding and unraveling the very old knot of white privilege.

Sources:

Leah Penniman, Four not so easy ways to dismantle racism in the food system

Ricardo Salvador, Holyoke Food Justice Conference

Food Research and Action Center, FRAC Farm Bill Action site (FRAC Newsletter, December 2017)

National Sustainable Agriculture Coalition, NSAC’s action link

Union of Concerned Scientists Food and Agriculture Program

USDA Economic Research Service

Catherine Sands, MPPA, is a food systems consultant, evaluator, facilitator, and educator living in Western MA. She directs Fertile Ground and is a food policy lecturer in the UMASS Amherst Sustainable Food and Farming program.