This post was originally published on the UNH Sustainability Institute blog.

This past Friday, July 29, I had the pleasure of visiting Rhode Island to gain a better understanding of the food landscape within the state. During a whirlwind twelve hours, I held four interviews with representatives from across the Rhode Island food system and, with the help of my tour guide Ken Payne, visited seven different sites to provide me with a historical and diverse picture of the Rhode Island foodscape.

Ken and I first discussed the possibility of visiting Rhode Island when we met at the 2016 New England Food Summit in early June. He currently serves as the elected chairman of the Rhode Island Food Policy Council and is also a member of the Network Team and the Process Team of Food Solutions New England (FSNE). Once we were able to settle on a date, Ken suggested I visit some food projects while I was in the area and volunteered to be my guide for the day. Little did I know how busy my trip to Rhode Island was about to become.

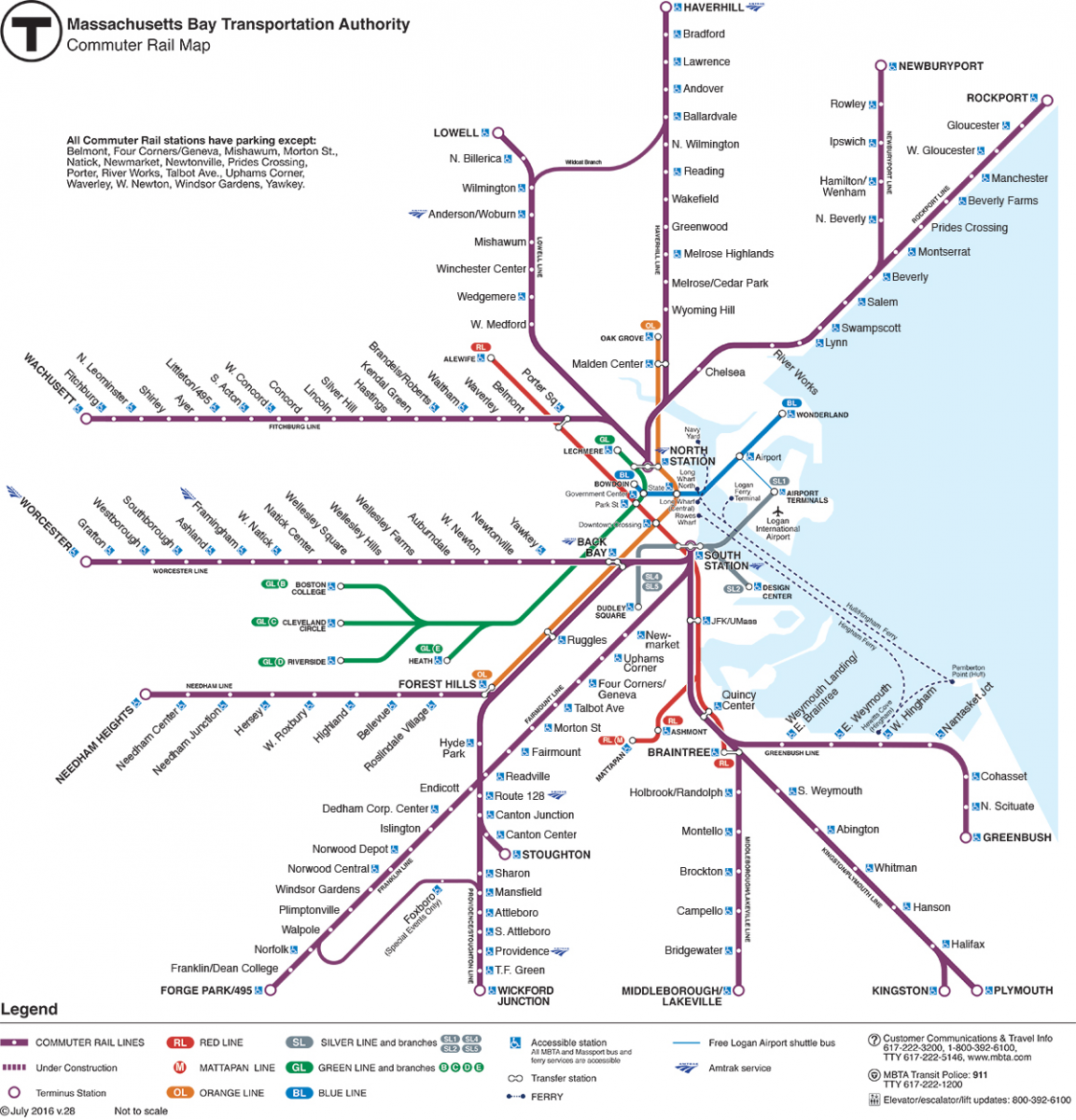

Throughout the day, Ken and I visited the fishing docks at Wickford Cove; a Seven Stars Bakery location in Providence; the Farm Fresh Rhode Island facilities located in the Hope Artiste Village, which also serves as the site of the Wintertime Pawtucket Farmer’s Market; the Port of Galilee in Narragansett; a new Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority (MBTA) stop, and countless roadside stops cross the southern half of the state representing important historical and/or agricultural sites.

To say that I learned a lot on Friday would be an understatement. While I am still trying to synthesize all of the different stories I heard, I am struck by one central theme that emerged throughout the day: the need to preserve and create spaces of food production. In particular, I will focus on my conversations with Ken and Julius Kolawole as they illuminated this point.*

My Friday morning began with a two-hour conversation with Julius Kolawole in the office of the African Alliance of Rhode Island (AARI). There are more than 75,000 African refugees from 40 different countries living in the state of Rhode Island[1]. One of the central initiatives of the AARI is to coordinate community gardens for the use of African refugee communities. When the first garden opened in 2009, AARI hoped that the gardens would allow refugee populations to grow foods with which they were familiar and which often weren’t available at local grocery stores or corner shops. Additionally, AARI encourages individuals to grow food in their homes, often providing the supplies for container gardens. By 2011, the garden projects were so fruitful that Julius encouraged the participants to sell at a local farmer’s market. The stall has become highly successful with a diverse customer base through a variety of outreach efforts, including giving out free vegetables with recipes for how to incorporate the vegetables into meals, and now also sells value-added products, such as relish made from the community garden vegetables. [2]

During my time with Julius, he had to stop to take a series of phone calls. He explained to me that AARI is in the process of setting up two more community gardens. However, there are already eighteen individuals on the waiting list to have a spot in a community garden. Even with the additional garden sites, Julius stated that there are more people who want to participate than they can accommodate. The existing garden projects mostly reside on unused lots, making the gardens appear to be oases of green in urban areas. Prioritizing space for food production will be a crucial project for AARI moving forward, and AARI has already leveraged support from local government and other non-profit organizations to dedicate more space for urban food production.

During my time with Julius, he had to stop to take a series of phone calls. He explained to me that AARI is in the process of setting up two more community gardens. However, there are already eighteen individuals on the waiting list to have a spot in a community garden. Even with the additional garden sites, Julius stated that there are more people who want to participate than they can accommodate. The existing garden projects mostly reside on unused lots, making the gardens appear to be oases of green in urban areas. Prioritizing space for food production will be a crucial project for AARI moving forward, and AARI has already leveraged support from local government and other non-profit organizations to dedicate more space for urban food production.

While Julius’s work with AARI emphasized the need to create space, Ken Payne talked to me about the need to maintain the existing agricultural spaces in Rhode Island. In order to illustrate this need, Ken and I drove down to southern Rhode Island. Our first stop was Wickford Junction, the final stop on the Providence/Stoughton Line of the MBTA Commuter Rail. While the railway has been in existence since the late-nineteenth century, the stop was renovated in 2012 as part of its incorporation into the MBTA system. The new station is easily accessible from Route 103, features clean, indoor facilities that are open 24-hours a day, and provides ample parking in an attached garage.[3] In 2015, Rhode Island Department of Transportation constructed a bus depot next to the parking garage and shifted a variety of Rhode Island Public Transit Authority (RIPTA) bus services to the new location. [4]

I was confused as to why Ken would want to show me a train station. I had always thought of increasing access to public transportation as a positive trend, and Ken had seemed distressed when telling me of a recent transformation of the station. What did this have to do with food and preserving agricultural land? Surely the smattering of wild strawberry plants that had gone unnoticed in the station gardens wasn’t the reason we were here. Ken assured me that there was a connection to be made, but we would need to drive a little bit away from the station.

Urging me to keep an eye on my odometer, we navigated away from the Wickford Junction station. In just a few minutes, Ken and I had driven into prime agricultural land: acre upon acre of fruits and vegetables being grown. I glanced at my odometer and saw that we had traveled a mere mile and a half from the Wickford Junction station. I began to understand why Ken had felt it was important to visit the train station first.

As we continued to drive by farms advertising pick-your-own blueberries, Ken explained to me that there were more than 2,000 acres dedicated to agricultural production within a six-mile radius of the station. Although these acres include some of the largest sod producers in New England, Ken stated that some of these producers realized the importance of growing food and had begun to shift their operations to growing fruits and vegetables for local consumption.

Ken explained that with the renovation of the Wickford Junction station, the area had become more desirable for people commuting to Providence or Boston to work. Population growth could shift the demand for land, potentially causing agricultural land to be converted into housing or businesses to meet the demands of a growing population. I recalled that near the junction of Route 102 and Route 5a, just over a mile from the station, there had been several lots of land for sale. Ken stated that those had been former agricultural lands but were now zoned as multiple-use lots; he was skeptical that they would remain in agricultural production. For Ken, these lots represented early examples of the potential ripple effect of the Wickford Junction renovation. The expansion of public transportation was far more nuanced than I had initially realized and had I been driving these roads by myself, I doubt that I would have made the connection between a train station and food production.

Ken explained that with the renovation of the Wickford Junction station, the area had become more desirable for people commuting to Providence or Boston to work. Population growth could shift the demand for land, potentially causing agricultural land to be converted into housing or businesses to meet the demands of a growing population. I recalled that near the junction of Route 102 and Route 5a, just over a mile from the station, there had been several lots of land for sale. Ken stated that those had been former agricultural lands but were now zoned as multiple-use lots; he was skeptical that they would remain in agricultural production. For Ken, these lots represented early examples of the potential ripple effect of the Wickford Junction renovation. The expansion of public transportation was far more nuanced than I had initially realized and had I been driving these roads by myself, I doubt that I would have made the connection between a train station and food production.

On Saturday, as I mentally unpacked the busy day prior, I realized that my conversations with Julius and Ken represented two sides of the same coin and both expressed a sense of urgency. If Rhode Island wants to support food production within the state, there must be space on which people can produce that food. My time with Ken demonstrated the need to be proactive in protecting the spaces were food production occurs while my conversation with Julius illustrated projects seeking to reclaim spaces for food production. The Rhode Island Food Policy Council (RIFPC) recently released a 2016 Update to their 2011 Food System Assessment and expressed the need to support the concerns raised by both Ken and Julius.[i] As the RIFPC moves forward with creating a statewide food strategy, I hope that these concerns and their urgency remain an integral component in the conversation. After seeing the vibrancy and commitment of so many diverse projects and individuals across the Rhode Island food system, I have no qualms about my optimism for the future of Rhode Island’s food system.

*In addition to Ken and Julius, I was privileged to speak with both Jesse Rye, the Co-Executive Director of the Food System Enterprise at Farm Fresh Rhode Island; and Leo Pollock, founder of The Compost Plant and the Network Coordinator of the Rhode Island Food Policy Council. The breadth of skills and dedication among these four individuals is impressive, and I thank them for the time they gave me.

August 04, 2016

Written By: Abigail Randall, Food Solutions New England Fellow

Abigail is a doctoral student in the sociology department at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville where she studies political economy and environmental sociology. Her doctoral research focuses on the efficacy of food security policy at local and state levels. In her free time, she enjoys hiking, listening to spoken word, and trying to keep her garden alive. A native to New England, Abigail is thrilled to be returning to the region to work with Food Solutions New England this summer.

[1] African Alliance of Rhode Island. 2016. Accessed July 30, 2016. http://www.africanallianceri.org/ [2] Bender, John 2015. Rhode Island Public Radio. Accessed July 30, 2016. http://ripr.org/post/ri-african-alliance-shows-regional-cuisine-pawtucket [3] Rhode Island Department of Transportation. 2012. Accessed July 30, 2016. https://web.archive.org/web/20130511055131/http://www.ri.gov/DOT/press/v… [4] Rhode Island Department of Transportation. 2015. Accessed July 30, 2016. http://www.ri.gov/press/view/26353 [5] Chintapalli, Sumana. 2016. Accessed on July 25, 2016. http://rifoodcouncil.org/2016/07/25/rifpc-releases-new-report-ri-food-sy…