The phrase “privilege is blind” is one I think about often. I’m participating in Food Solutions New England’s 21-Day Racial Equity Challenge for the second year because I need to see beyond the blinders of my experience. I recognize that a person of color would not have to set an intention to learn about racial injustice and equity; it is their lived experience. As a white person, raised in white suburbs, working and living within social networks that are largely white (e.g., research shows white Americans have social networks that are 91% white,) I humbly recognize how much I have to learn.

Good intentions are not enough. In 18 Things White People Should Know Before Discussing Racism the author states: “Discussions about racism should be all-inclusive and open to people of all skin colors. However, to put it simply, sometimes White people lack the experience or education that can provide a rudimentary foundation from which a productive conversation can be built. This is not necessarily the fault of the individual, but pervasive myths and misinformation have dominated mainstream racial discourse and often times, the important issues are never highlighted.”

If I want to constructively work for change, I have to start by wading through this misinformation and myths. When Van Jones wrote about Black Lives Matter activists disrupting Bernie Sanders events, he noted how few progressives have “focused on building authentic bridges beyond their monochromatic comfort zones.” By not being tuned in to the daily lives of people of color, “their prescriptions for change often ring hollow and fall flat — at least outside their own company.”

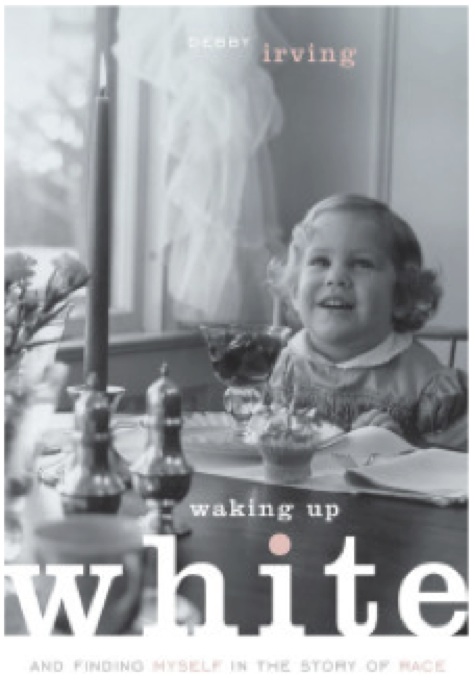

In last year’s Challenge I read Debbie Irving’s book Waking Up White, which offered a foundational course in understanding how the world I see from my white experience is skewed. She openly shares her series of wake up calls, mis-steps, and deepening learning about race and what it means to be “white.” The following story Irving shared was a wake up call for me about how fragmented the narratives of history can be.

In last year’s Challenge I read Debbie Irving’s book Waking Up White, which offered a foundational course in understanding how the world I see from my white experience is skewed. She openly shares her series of wake up calls, mis-steps, and deepening learning about race and what it means to be “white.” The following story Irving shared was a wake up call for me about how fragmented the narratives of history can be.

Irving was in a graduate course called “Racial and Cultural Identity,” when the class watched a video called Race: The Power of an Illusion. It described how, when it was first instituted, the GI Bill offered returning veterans free access to higher education and low interest housing loans; however, only about 4% of the one million black GIs were able to access the benefits of the GI Bill’s free education. Colleges had limited quotas of how many blacks they would accept. Blacks’ access to the housing benefits was blocked. Policies of the Federal Housing Authority, implemented by realtors and bankers, “redlined” houses and neighborhoods. The result: between 1934 – 1962, the federal government underwrote $120 billion in new housing with only 2% going to blacks. Another federal program, Urban Renewal, demolished inner-city neighborhoods to make way for interstate highways, eliminating 90% of low-income housing.

In Irving’s experience growing up in a well off white household, the GI bill was praised as a great success. The policy helped her father and uncles, as returning vets, to get a free college education and subsidized their first house mortgages. No one ever mentioned that this was all denied to blacks. Irving writes: “America’s largest single investment in its people, through an intertwined structure of housing and banking systems, gave whites a lifestyle and financial boost that would accrue for decades to come while driving blacks and minority populations into a downward spiral.”

When she learned this, she said it “hit her like a ton of bricks” and it hit me that way too, realizing the scale of how racism was institutionalized in our larger systems. The world around us now is created by the implications of those racist policy decisions decades ago, which enabled one group to thrive and condemned another to poverty. I could see this was my story too, as someone who grew up benefitting from all the things these policies enabled. And I wondered, why I never fully appreciated the scale of this; why wasn’t that common knowledge?

The GI Bill and redlining are only one of many examples, the more I am learning. I realize if we want to change systems and seed new ones based in the values of equity, we must investigate the deeper roots and structures that give rise to current events.

Beth Tener is a facilitator and coach, working with various social change initiatives around New England through New Directions Collaborative.